“Misquoted,” Journalistic Carelessness Starts Small

All the words between quotation marks are exactly what people said—sort of. For the Depp v. Heard defamation trial, we see a screenshot that says otherwise.

Intro

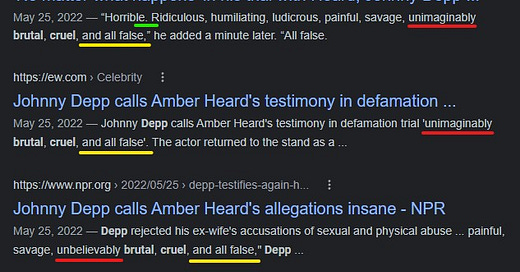

Look at this screenshot of Google search results regarding the Depp v. Heard defamation case. The color-coded markups show differences between multiple media sources’ reporting in direct quotes of Johnny Depp’s spoken response at trial.

Evidence

Exhibit A

Discussion

Mainstream media sources made a mistake, getting the info in direct quotations wrong.

This is called misquoting—it’s academic/professional misconduct, and it’s illegal.

In writing classes at universities, including journalism courses, professors teach students that misquoting is plagiarism, a punishable offense even if accidental.

You might look at the differences in the screenshot and think close enough, not nearly at the level of misinformation. Legally speaking, a US court would probably rule in your favor (I’m not a lawyer; never take anything I write as legal advice).

According to US law, misquoting someone is illegal but only if the words meaningfully differ, if the misquoting was done with malice, and if the misquoted party suffered provable damages.

Such legal latitude has emboldened a journalistic attitude that misquoting doesn’t matter.

However, controversies have broken out over being misquoted. And guides exist online to prevent a journalist misquoting you.

Here’s a bit of irony for the screenshot. During the defamation trial, Amber Heard used the words “pledge” and “donate” synonymously, leading to a debate about word choice between Depp’s attorney Camille Vasquez and Heard. Vasquez later said in her closing arguments, “words matter.”

The irony compounds when you consider how this defamation case, in part, involved the exact words quoted in mainstream media publications.

Indeed, misquoting a source is technically unprofessional for journalists. Quotes are meant to be exact. Exactness reflects work ethic and moral ethics.

But misquoting in journalism is quite common and has been for some time. The fast-paced nature of reporting the news, alongside how our brains recode information for storage, make verbatim repetition highly troublesome.

That said, misquoting has little excuse in the age of digital media. Not that it had much excuse in the age of analog media either (reporters carried cassette recorders for a reason).

You see, the screenshot shows mainstream media publications getting exact quotes incorrect from a courtroom testimony which was exactly recorded by a stenographer. Even when we account for the urgency of breaking news, without time to wait for the transcription, remember this:

The words in question were available live, on YouTube, in a clearly recorded, freely accessible, infinitely replayable, closed-captioned video from multiple sources. Outlets even released clips highlighting that specific moment in which the words were spoken. To misquote in an article with the clip embedded is even worse.

Further, in an era of news aggregation and copy-paste journalism, when publications republish competitors’ articles, it’s bizarre for so many media sources to disagree about the exact words someone said. Ironically, direct quotes are the one thing that you must copy and paste to avoid plagiarism!

So why, then, does misquoting continue in digital media? Carelessness, it seems. Time is money, and exactness isn’t worth the time, despite how easy exactness is to achieve with digital media. If a misquote is legally safe, it’s faster to publish and move on. Most people won’t notice, and fewer will care about the people who do notice.

Conclusion

When you read someone who was quoted in the media, you’re trusting that their exact words were inside those quotation marks. But we’ve seen an example where that wasn’t the case. While the evidence here strongly suggests no bias occurred, carelessness certainly did occur, and that can be just as unfair both to the person misquoted and to the readers.

Imagine if someone was misquoted whose words weren’t recorded for the public to hear on demand. In this post’s example, the differences might be close enough, but how would you know if it’s close enough if you don’t know what was actually said? Someone else is determining that for you.